اخبار العرب-كندا 24: الثلاثاء 30 ديسمبر 2025 09:08 صباحاً

If Canadians have ever felt like they had a handle on who goes to jail, when and why, and for how long, it’s tough to believe they do nowadays. Or if they think they do, chances are good they’re not too happy about it. Once you notice how many news stories there are about people who have been accused or convicted of violent crimes, and then gotten out on bail or parole, and then been latterly accused or convicted of further violent offences, it is quite difficult to un-notice it.

Whatever you thought about the Freedom Convoy that took over downtown Ottawa in 2022, it was remarkable to see the Crown ask for sentences of up to eight years for the organizers’ non-violent offences. Ottawa Police should have been able to prevent all that from happening, with frankly minimal effort. And eight years is a considerable sentence in a Canadian court.

Compare that to what happens with some unambiguously violent offenders.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

In July, the Crown recommended a sentence of seven to nine years for 29-year-old Jamal Joshua Malik Wheeler, who fatally stabbed total stranger Rukinisha Nkundabatware, a 52-year-old Congolese refugee and father of seven, at an Edmonton transit stop in 2023. Wheeler’s previous offences included attacking three other random strangers on the transit system, in one case brandishing an axe.

Earlier in July in Vancouver, Provincial Court Judge Susan Sangha approved the Crown’s sentencing recommendation for Zachary Shettell, whose hobbies include consuming opiates and punching random strangers in the face, leaving them writhing in pain on the sidewalk. He had pled guilty to sucker-punching three strangers, as well as pouring hot coffee on a bank teller. His record was 27 convictions long, including three for assault. He rejected any need for counselling or treatment for his admitted substance-abuse problems and denied he had any psychiatric issues.

Shettell’s court-approved sentence was 18 months.

Later in July, the Crown in Ontario decided 240 days in pretrial custody had constituted sufficient incarceration for a 17-year-old girl, 14 at the time of the crime, who was convicted of manslaughter in the fatal “swarming” attack by feral teens and tweens on Kenneth Lee, a homeless man who was just minding his and his down-on-their-luck friends’ business in downtown Toronto. Should she ever reoffend, thanks to her young-offender status and the adamantine publication ban on her name that comes with it, it’s likely the public would never know about it.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

The government’s latest National Justice Survey, from 2023, did not suggest Canadians were very confident in their justice system at all. On a scale of one to five, one being least confident and five most, just 18 per cent of respondents registered a four or five on confidence that the system was “fair to all people,” and just 23 per cent that it was “accessible to all people.” That seems pretty dismal, no?

An Abacus Data poll conducted late in September reported 80 per cent of respondents agreeing that “individuals with a history of repeat violent offences should be automatically denied bail for serious charges.” The poll found plenty of support for addressing the root causes of crime, but even more for “implement(ing) stricter laws and penalties for certain crimes.” Clearly, that is not what they are seeing.

Basically, Canadians don’t seem to understand the justice system from any perspective at all. What they do understand about it, they don’t seem to like. And bail, parole and plea bargains seem to be among the most misunderstood parts of that system.

This being Canada, where governments generally treat long-term comparable data like demons and alligators, we don’t have a lot of data with which to judge the scope of this problem accurately. We don’t keep comprehensive statistics on plea bargains, for example, which are one of the most contentious but also most essential elements — for better or for worse — of the legal system.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Estimates of how many criminal matters are resolved through plea-bargain negotiations in Canada begin at 90 per cent and go up from there. And no one disputes that without them, the criminal justice system would be in big trouble. We simply don’t have the resources to finalize all the charges that police lay, and prosecutors pursue, in trials.

“It goes without saying that plea resolutions help to resolve the vast majority of criminal cases in Canada and, in doing so, contribute to a fair and efficient criminal justice system,” Supreme Court Justice Louise Charron wrote in a 2011 decision. Those pleas usually involve joint sentencing recommendations from the Crown and defence.

A memorial for Rukinisha Nkundabatware at the location where he was stabbed to death by a stranger in Edmonton. Prosecutors recommended a sentence of just seven to nine years for his killer.

For fans of courtroom procedurals on TV, this might seem a bit odd. A plea bargain on Law and Order is often a crazily adversarial process: the assistant district attorney of the day might demand quick death by firing squad, while the defence insists on an absolute discharge and a written apology from the governor. (I exaggerate only somewhat.) In such plot lines, the power dynamic often pivots almost entirely on the defence attorney’s hourly rate or idiosyncratic genius, with most public defenders practically at the prosecutor’s mercy.

There are certainly similar concerns in Canada about the power of the Crown.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

“In the plea-bargaining process, prosecutors hold a great deal of power and authority, and the absence of substantial ‘oversight mechanisms or procedural safeguards’ gives rise to apprehensions about arbitrariness and inequality,” Sharmi Jaggi, counsel for the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission, wrote in a paper last year published in the UBC Law Journal.

But former federal prosecutor Rob Dhanu, now a criminal lawyer in B.C., sees significant differences between the Canadian and American realities. The former is “adversarial,” he says, but the latter is “truly knives-out.”

“The stakes are extremely high (in the U.S.) not only with capital punishment on the cards but extremely long sentences if one does not accept often unpalatable plea offers,” Dhanu argues. “This cutthroat approach … increases the opportunity for very significant miscarriages of justice, both in quality and quantity.”

If some perceive a prosecutor’s job as getting the maximum possible sentence in every case, legal scholars broadly agree that’s not a Crown prosecutor’s designated role in Canada. It’s more about getting to the truth — in theory, at least.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

“The Crown works for the public interest. In many cases, the public interest is best served by a fast and certain resolution, especially when other more pressing cases may require more resources or may be approaching unconstitutional delay issues,” says Queen’s University law professor Lisa Kerr, an expert in criminal sentencing. “Or when a longer sentence won’t serve any useful purpose.”

(Now we just all need to agree on what’s a “useful purpose”!)

London, Ont. criminal defence attorney Nick Cake, a former Crown prosecutor, suggests Canadians at large should perceive the defence-prosecutor relationship as “two lawyers trying to do all they can for their side, bound at a minimum by the rules of procedure and the rules of evidence, negotiating in a system that promotes plea negotiations given the scarcity of its resources.”

These day-to-day practicalities are a long way from the simplistic political “tough-on-crime” discussion, which generally frames cracking down as a relatively simple matter of determination: A Conservative government will do X, a Liberal government will do Y.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

There is moral peril in using plea bargains simply as a way of ploughing the road to a resolution

In November, mustering all his considerable chutzpah — or is it just a total lack of self-awareness? — Justice Minister Sean Fraser admonished “all parties to … put politics aside” and get behind tougher bail conditions. Fraser’s Liberal government spent much of the Justin Trudeau era deriding anyone advocating anything of the sort as a troglodyte — even those who pointed out that it was insane to transfer child-murderer Terri-Lynne McClintic to a zero-security “healing lodge.”

The primary, largely unacknowledged complexity in the Canadian tough-on-crime discussion is jurisdictional: The feds write the law, and that’s where the vast majority of media attention gets focussed. But it’s the provinces, mainly, who prosecute the law, or don’t, and set the rules and guidelines for prosecutors — and they’re laser-focused on efficient outcomes we can (supposedly) live with, as opposed to any kind of perfection.

“Negotiated resolutions are a form of dispute resolution that … reduces unnecessary litigation, system delays, inconvenience to victims and witnesses, and overall public expense,” the Alberta attorney general’s guidelines for Crown prosecutors advise.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Saskatchewan’s guidelines state much the same.

“Prosecutors are strongly encouraged to initiate and participate in resolution discussions at the earliest opportunity,” British Columbia’s Crowns are advised.

“The prosecutor must consider all available and appropriate sanctions, consistent with public safety, to resolve cases as early as possible,” Ontario’s Crown attorneys have been advised since 2020.

It’s true among federal prosecutors as well: “Early and meaningful resolution discussions between Crown counsel and defence counsel are an essential part of the criminal justice system,” the Public Prosecution Service of Canada Deskbook explains.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Occasionally, judges overrule sentences negotiated by prosecutors and defenders as too lenient. In April, Ontario Court justice Angela McLeod kiboshed 120 days for a man who broke into a home and then tried to disarm a police officer of his taser, as well as punching a second police officer, and also bank fraud.

“I find that the joint submission is so ‘unhinged from the circumstances of the offence and the offender that its acceptance would lead reasonable and informed persons, aware of all the relevant circumstances, including the importance of promoting certainty in resolution discussions, to believe that the proper functioning of the justice system had broken down’,” McLeod wrote, quoting a Supreme Court decision codifying when judges may reject such agreements.

But judges making a call like that is a rarity.

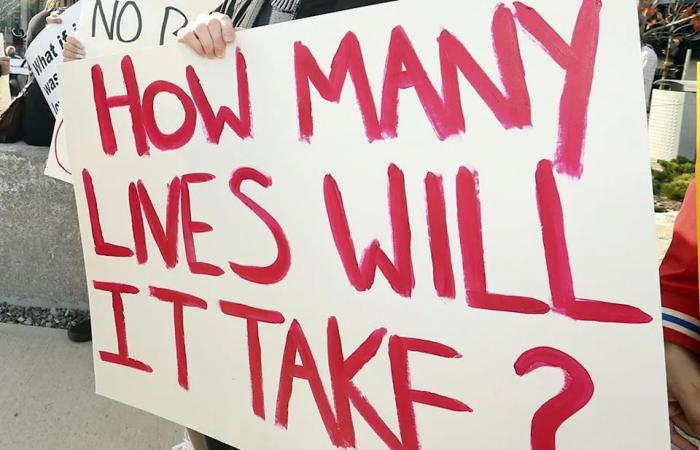

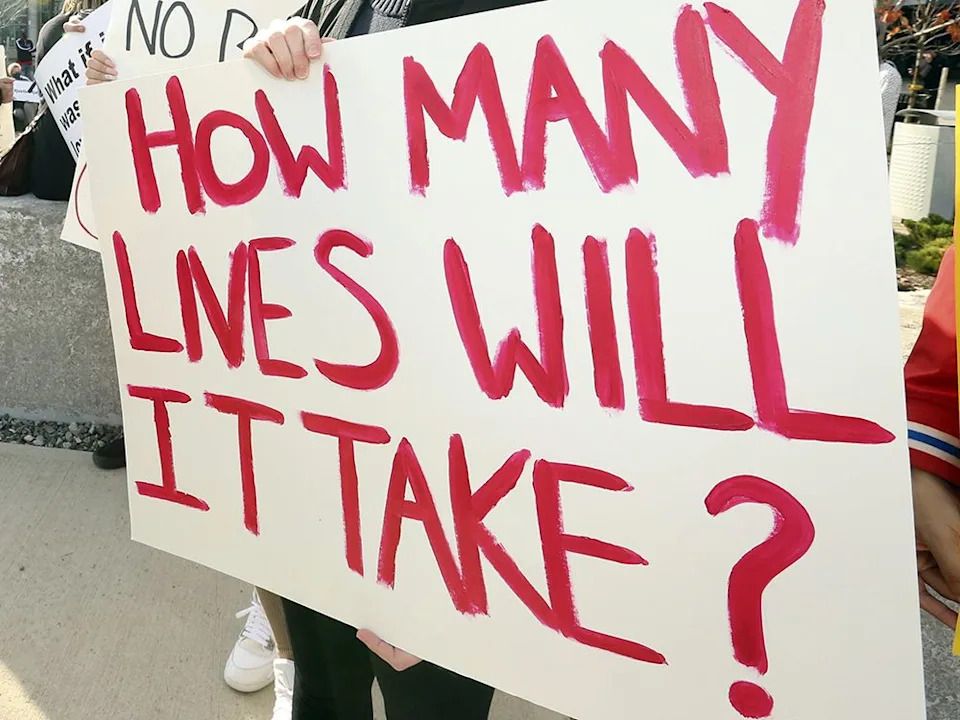

A recent poll reported 80 per cent of respondents agreed that “individuals with a history of repeat violent offences should be automatically denied bail for serious charges.”

There is moral peril in using plea bargains simply as a way of ploughing the road to a resolution. It has an air of casualness about it, like haggling over a used car, that ill befits such a key element of a functional society. Taken too far in favour of the defendant, it risks undermining public confidence in the justice system.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

And at some point, Canada’s financially straitened justice systems are likely to become a serious political peril as well. Someday, a murderer or other violent criminal will get off scot-free because the system couldn’t organize a trial in time to prevent violating the accused’s right to a speedy trial, and the judge will throw out the case, and that accused will go out and murder someone very sympathetic. The federal Ombudsman for Victims of Crime reported in November that hundreds of cases of sexual assault had to stop being prosecuted because the accused was not tried in a reasonable length of time, per the Supreme Court’s 2016 Jordan ruling. (Some of the trials were aborted even after the alleged victims had to endure testifying.)

In every sense, speeding up the system is the most conspicuous Job One. But if our justice systems had more resources — judges, clerks, prosecutors and courtrooms; and of course if it ran efficiently — what would we do with them? Might more cases go to trial — ideally from people with the most compelling defences or indeed who are innocent — and fewer resolved via plea?

Cake, the defence lawyer, doubts it. “If there were more courtrooms and more judges there may be more matters that are set for trial, given that there would be less time to get a matter to trial and thus less time for the accused to live on release conditions,” he says.

But, he adds, “plea bargains are more often the product of the facts of the case and the rules of procedure and evidence (than of expediency).”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

“More resources could impact the plea bargain process but only if they were allocated in a more mindful manner that we do now. Before allocating further resources, we need to conduct a top-to-bottom reassessment of our justice system,” says Dhanu, suggesting we focus in particular on gathering statistics (so we know what’s actually going on) and on keeping people out of the justice system in the first place.

For those who really want Canada to get tougher on crime, the solutions are much more likely to be part of that “top-to-bottom reassessment” than any single bill that lands in Parliament.

National Post

cselley@postmedia.com

تم ادراج الخبر والعهده على المصدر، الرجاء الكتابة الينا لاي توضبح - برجاء اخبارنا بريديا عن خروقات لحقوق النشر للغير