اخبار العرب-كندا 24: الخميس 11 ديسمبر 2025 07:08 صباحاً

This article is part two of a series of stories about the drug crisis in Hay River, N.W.T. Read part one here.

Cindy Caudron pulled up to an ATM in downtown Hay River, which some people use as a place to sleep.

“There’s usually eight or nine people here, and they rotate … I’m just going to check and see how they’re doing," she said.

She found two people stretched out on the tile floor.

“Auntie!”, one yelled when she saw Caudron. After taking an order for a couple of French vanilla coffees, Caudron hopped back in her truck.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

“I don’t know if I’m her auntie. In Indigenous culture, when there are people who are older, we just call them aunties," she said.

Caudron has been making her rounds in the N.W.T. community since she noticed the town’s drug crisis start taking hold a few years ago.

“I do this at least four times a week, and at lunchtime,” she said.

Caudron is not part of an organization, and this is not her job.

“I grew up here, never saw this kind of thing before. We used to have people with just alcohol problems … [not] crack cocaine, heroin, crystal meth and that kind of thing.”

She’s worried about a divide she sees in the community between people who struggle with addiction, and everyone else. She said people in Hay River are very caring.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

"But I think they don't know what to do about the drug trafficking and the violence and break-and-enters and guns."

She spends her nights giving hugs, and dropping off cookies and coffee, trying to bridge that divide.

Not 'solving the larger issue'

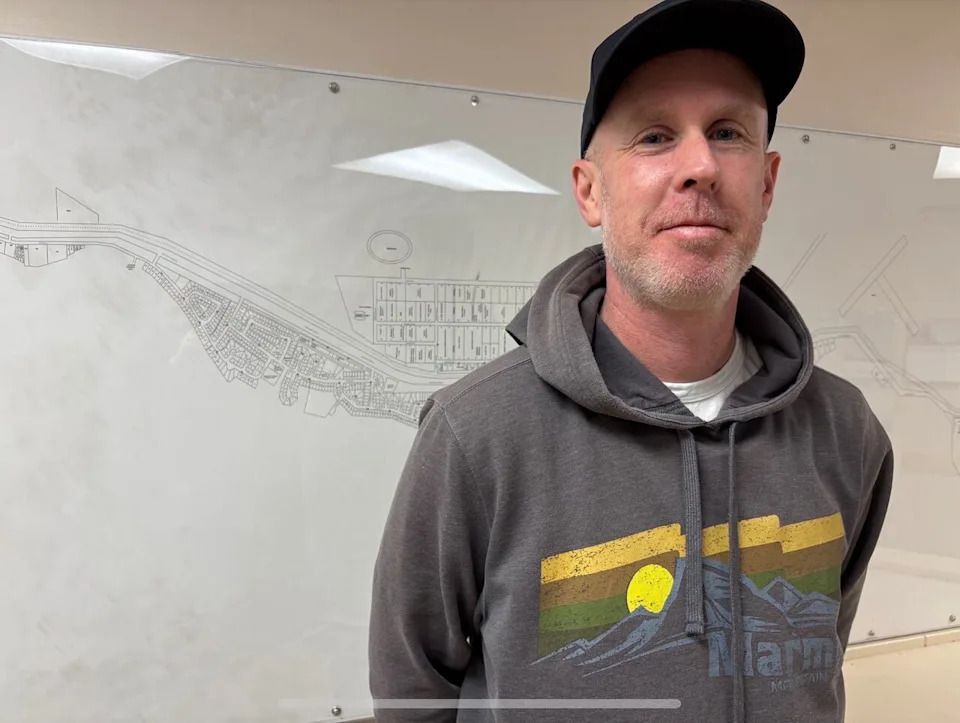

Evictions from public housing are at an all-time high in Hay River, said Adam Swanson, the acting manager of the Hay River Housing Authority. It's something he ties to the drug crisis.

Swanson said some nights he doesn't sleep so well.

“I’m keenly aware you are taking away one of the key factors of life.”

From the more than 12 families he's had to evict this year, he’s noticed a trend.

(Marc Winkler/CBC)

“Once the addiction sets in, obviously there's a money factor that comes with that. And I think to generate that money, the only option is to begin selling [drugs] yourself, or to allow somebody … to be in your unit and use it for that purpose.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Swanson said evictions are his only option for protecting the public.

“We have families that don't feel safe in their homes, families that don't feel safe with their children playing outside, families who have called and told me that their children are sleeping in their parents' bedroom at night because their window may face a unit that's experiencing these kinds of problems. And it's terrifying.”

He said that evictions “aren’t solving the larger issue.” Over the last few years he said the problems have, frustratingly, moved from one section of town to another.

“We keep plugging away and we feel like we're successful … Until the next one rears its head and it's like starting all over again.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Swanson said the community needs better housing options, like a shelter that offers people their own apartments.

"Just something that's going to protect vulnerable people from being taken advantage of," he said. "Protecting not only the community, but protecting people from themselves.”

The effect on children

Some of the most devastating effects of the drug crisis in Hay River have been on children.

“If the drug is being smoked in the house, I'm assuming the child is ingesting a lot of that smoke,” said one foster parent who CBC News is not naming to avoid identifying any of the children in her care.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

“They cry a lot. They hurt a lot. They don't want to be touched. Some don't like the light, and as for eating, they eat very little.”

The woman cleared pencil crayons and juice boxes off her kitchen table to make some space for her cup of tea.

She said the hardest part of fostering these children is managing the relationship between them and their birth parents.

“I don't sugarcoat it for the kids ‘cause when we go shopping we see parents on the street, we see them in the condition that no child should see them in.”

She said the town is lacking enough foster homes, and enough support, to help children get involved with their birth parents. She thinks people dealing with addictions need more direct support too.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

“Set up some warming centres, some day jobs, so they can get off the streets and be productive again …[so they can] have some dignity back. You know, they are stripped of everything.”

Drugs changing a library

Another sign that Hay River has changed in recent years is in how the library greets its patrons. The building is in the center of town, and set back from the sidewalk by a large snowy lawn.

Marnie Kruger is the library’s acting head manager. She said two years ago, she had to remove chairs and access to washrooms, among other things.

Marnie Kruger is the acting manager of Hay River's library. The drug crisis has had a deep, personal effect on her life. (Marc Winkler/CBC )

“There would be fights and people would be getting more and more inebriated or high as the day went on ... and you know, our pamphlet says we're the living room of the town.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

For all the stress it caused her, Kruger doesn’t blame the people who were causing disruptions.

“I feel for some of the people that have been longtime abusers. Sending them out for treatment is not the answer … you send them out for 30 days and they come back. But they come back to what? They have a reputation in town, so probably not going to get a job. They’re gonna go back to their friends. They’re gonna go back to what they know. It’s just what’s going to happen.”

The drug crisis has had a far deeper effect on Kruger’s life, beyond the changes she has overseen at the library.

“My daughter was murdered five years ago. And it was somebody under the influence, a friend of hers,” she said. “It should never have happened.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Kruger said her faith and family helped her through the loss, things that also help her feel compassion when she sees others wrapped up in addiction.

“They're all human beings. They're all people. They’re somebody's daughter or sister or mother or whatever. And there but for the grace of God go I.”

LISTEN | Part 1 of CBC North's series on Hay River's drug crisis:

تم ادراج الخبر والعهده على المصدر، الرجاء الكتابة الينا لاي توضبح - برجاء اخبارنا بريديا عن خروقات لحقوق النشر للغير