Arabnews24.ca:Saturday 29 July 2023 01:10 PM: The Hollywood blockbuster film Oppenheimer is exploding in theatres with sellouts and enthusiastic reviews, but a Winnipeg connection has remained behind the curtain.

The film chronicles the life of Robert Oppenheimer, a theoretical physicist who headed the top secret Manhattan Project, which ushered in the Atomic Age.

Oppenheimer was director of the Los Alamos lab where the work was done, but it was Louis Slotin, from Scotia Street in Winnipeg's North End neighbourhood, whose fingers assembled the plutonium core of the first atom bomb, the Trinity Gadget.

"He passed away before I was born, so I never met him in person, but my family always told me about him and I viewed him as being very brave and someone who should have been a hero," said Israel Ludwig, whose mom was Slotin's sister.

Trinity was dropped at a New Mexico desert test site on July 16, 1945. Its success led to the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki being bombed a month later.

The exact number of deaths from the atomic bombings remains unknown but it is estimated 120,000 people died instantly while tens of thousands more died over the next several months from burns, radiation sickness, illness and malnutrition, with an estimated total of 129,000-226,000.

The Oppenheimer film includes a short black-and-white clip of Trinity being assembled, and in the centre is Slotin, "although his name isn't mentioned, there's no credits given," Ludwig said.

His deftness at bomb-making earned Slotin the nickname "chief armourer of the United States," said journalist Martin Zeilig, who wrote articles and made a documentary about Slotin.

"But you won't find Louis Slotin mentioned in many of the biographies of the Manhattan Project. He was working with all these giants of science," Zeilig said.

"When you're in that rarefied atmosphere, it might be difficult to get your name into the history books.

"That's one of the main reasons to tell this story and educate a new generation about the role of this scientist from Winnipeg. He was an amazing guy. I'm actually getting quite emotional thinking about it."

Born in the North End, the academically gifted Slotin entered the University of Manitoba at 16 and obtained his master of science degree by 22. He earned a PhD in physical chemistry in England in 1936, when he was 25.

He joined the University of Chicago and helped build the first cyclotron in the U.S. Midwest before being recruited to the Manhattan Project as the head of the team developing the plutonium core.

A year after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Slotin's team had one core remaining. It was for a third atomic bomb, but Japan surrendered and ended the war.

The core was kept and used for nuclear fission studies.

Slotin no longer wanted to be involved in projects meant for destruction and had given his resignation notice, Ludwig said.

"He wanted to go back to University of Chicago. He was taking interest in the use of radiation to combat cancer and he wanted to look into further uses … to help fight disease," Ludwig said.

Just before 3:30 p.m. on May 21, 1946, Slotin was showing colleagues how to bring the core close to a fission reaction, a procedure known as tickling the dragon's tail.

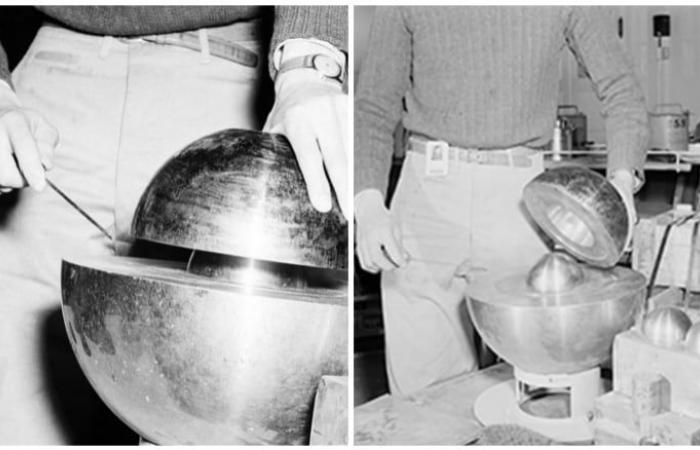

It involved placing two half-spheres of beryllium around the core. As the halves closed in around the core, the amount of fission intensified, bringing the materials to the edge of a nuclear chain reaction in what's called a criticality test.

Slotin used a screwdriver to maintain a gap between the halves. He had performed this procedure several times before, but this time the screwdriver slipped. The two halves contacted and caused an immediate critical reaction.

A flash of blue light and heat hit the room, according to the Los Alamos National Laboratory and Los Alamos Historical Society.

Slotin put his body in front of the sphere, shielding his fellow scientists, and yanked apart the two halves, halting the chain reaction before it could reach supercritical stage and trigger an explosion.

The exposure lasted about a second but was lethal for Slotin.

He was exposed to almost 1,000 rads of radiation, far more than the 400-450 considered a lethal dose, according to a 2016 article, Dr. Louis Slotin and the Invisible Killer, written by Zeilig for Canada's History magazine.

Slotin was rushed to hospital and died nine days later. He was 35.

His body was so scorched by the radiation, internally and externally, one medical expert called it a "three-dimensional sunburn," Zeilig's article says.

The seven other people in the room received an estimated 90 to 166 rads of exposure. All survived.

"Without a moment's hesitation, knowing the injury he would face, he dove into it to stop the chain reaction. You can't think of a higher sacrifice than to sacrifice your own life to save others," Ludwig said.

The plutonium orb, which had been playfully named Rufus before the incident, became known instead as the demon core.

The U.S. government declared Slotin a hero for his sacrifice, though some have debated that, saying his carelessness caused the accident.

"They already had mechanical procedures to do it, but he was a hands-on person and he wanted to do it himself," Zeilig said. "I say it lovingly. He was this risk taker."

He was also "this amazing mind," a Jewish kid from the North End who contributed to a defining moment in the history of human civilization, Zeilig said.

And that's how he wants people to think of Slotin: "That he played a key role in advancing that science and knowledge, for better or for worse."

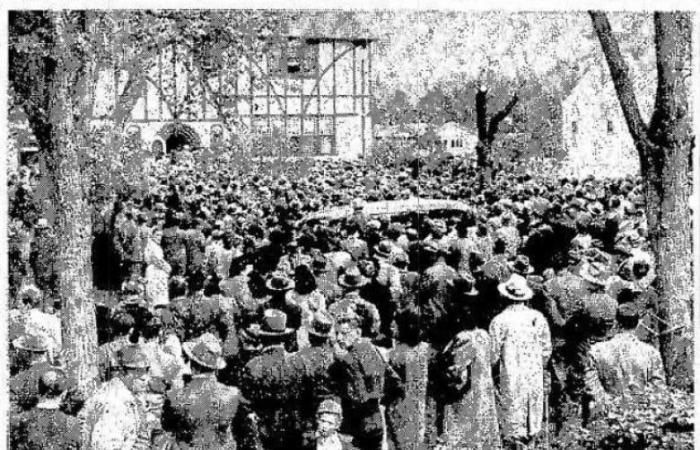

Slotin's funeral on June 2, 1946, was held at the family home, as was Jewish tradition. Thousands gathered to pay their respects, a Winnipeg Tribune article said the next day.

There were so many people outside the house, "you couldn't see the yard, you couldn't see the street," Ludwig said.

Before Slotin was buried in Winnipeg's Shaarey Zedek Cemetery, the rabbi called him "one of Winnipeg's most distinguished sons," the Tribune article said.

Following the accident, the Los Alamos lab ended all hands-on critical assembly work. Subsequent criticality testing of fissile cores was done with remotely controlled machines.

The facility where it happened is now called the Slotin Building. It has been preserved by the Los Alamos National Laboratory and is part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park.

In Winnipeg, Dr. Louis Slotin Memorial Park stands at the foot of Luxton Avenue, overlooking the Red River.

The small space, with benches and a plaque, is half a block from the former Slotin home on Scotia.